Had it survived the collapse of state socialism, the German Democratic Republic would be commemorating its 66th anniversary today. A month before the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the GDR held a massive celebration for East Germany’s the 40th year as a separate country. By the next year, politicians from both East and West worked together to make sure the GDR ceased to exist on October 3rd, in part to avoid the awkwardness of reaching 41.

Twenty-five years later, as the unified Germany dominates the political and economic landscape of Europe, alternatives to this status quo seem unthinkable. While the continued existence of the GDR has recently been the subject of no less that three speculative novels, contemplating such an idea is usually geared towards parody and humour.

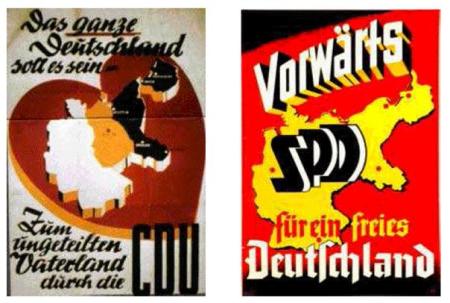

When we talk about German reunification, it is important to remember that the country created in 1990 looked very different than that sought as the division of the two Germanies was being formalized in 1949. In Western political posters from that year, the Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) both clearly supported the return of all lost territory in the East including that annexed to Poland and the Soviet Union in 1945.

Left: It should be the whole of Germany. For an undivided fatherland through the CDU. Right: Forwards, SPD for a free Germany

Into the 1960s, the Committee for an Indivisible Germany, a group supported by the West German left and right alike, produced propaganda material calling for the return return what was then the Western half of Poland as well as Kaliningrad.

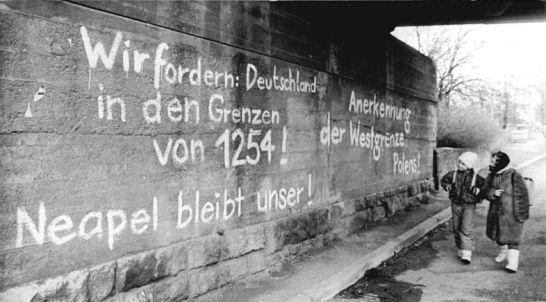

By the 1980s, the idea that reunification would include lands beyond the Oder-Neisse line that separated the GDR from Poland had moved to the margins. There was, however, enough discussion of the idea to inspire this graffiti in Jena mocking demands for a return to 1937 borders.

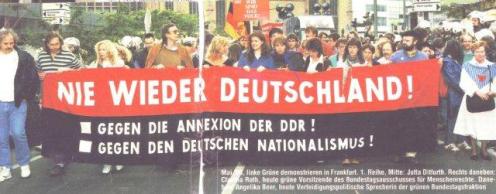

While the slogan “We are one people” was common to demonstrations in the GDR, there was also a small but vocal minority from East and West denouncing any plans for reunification.

The Never-Again-Germany (Nie-Wieder-Deutschland) movement held several conventions with thousands of participants, beginning in May 1990 and held its final demonstration in Berlin on the one-month anniversary of reunification.

Likewise, some in East Germany saw West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s overtures for rapid reunification as the beginning of a West German takeover. Just as the people of the GDR were gaining control over their country, there were fears that a “sell-out” to the West would jeopardize all that had been gained.

What I find most fascinating from this era is the draft constitution for a democratic East German composed by the Central Round Table – a forum comprised of state and party representatives and members of various dissident and civic movements created in December 1989. By creating a democratic constitution for East Germany, the Round Table hoped to fashion a clear alternative to Kohl’s plans for a rush to unity and set the stage for a reunification of equal nations

As Inga Markovits has argued, the draft was not a rebuke to the West German Basic Law but rather an attempt to surpass it by “moving towards a more participatory, more culturally diverse, more inclusive and more tolerant democracy.” The first article of the Constitution copies that of the West German Basic Law “Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.” The rest of the first 40 articles codifies democratic socialist conception of human rights. Alongside extensive guarantees for political and civil liberties, both as freedoms from the state as well as positive mechanisms to allow for greater participation through direct forms of democracy there was an emphasis on social rights for the elderly, disabled and unemployed.

Many of these provisions echoed the promises of earlier socialist constitutions including restrictions on free speech in the case of “war propaganda” and limitations on the amount of farmland that could be held privately. At the same time, many sections were written in response to the censorship and invasive surveillance of the GDR, cultural and academic freedom are enshrined as crucial rights alongside extensive provisions on privacy and due process.

On the issue of women’s equality and access to abortion, the Central Round Table also explicitly challenged the West German status quo. It sought to ensure substantial gender equality through bodily self-determination, state sponsored child-care and equal pay also featured prominently. While in the Federal Republic, abortion was legally restricted on the basis of the right to life of an unborn child, Article 4, Section 3 of the East German draft said “women have the right to a self-determined pregnancy. The state will protect unborn life through the offer of social assistance.”

In the end, the new democratically elected East German government rejected the constitution in the spring of 1990 and the GDR was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany as five new provinces. While there were some who dreamed of an abstract utopia of democratic socialism, the Central Round Table’s draft constitution went far beyond such notions to create an actual blueprint for what such an political and social order could look like. The draft Constitution provides a glimpse into an alternative democratic vision of human rights and democracy in Germany that did not come to pass.

The fact that there was foreign concern about the idea of reunification is now held up by some in the German media as a kind of betrayal. But I think it is more important to remember how implausible reunification seemed across the West up until the Berlin Wall was opened. In 1989, the British historian Donald Cameron Watt predicted “there will still be two Germanies fifty years from now.” In the same year, former US President Nixon contacted President George Bush to dissuade him from negotiating a reunification of Germany with the Soviet Union arguing that “The recent loose talk about the ‘inevitability” of German unification is irresponsible.” One can find similar rhetoric from many prominent intellectuals and politicians at the time indicating just how far from self-evident the eventual outcome of 1989 would be.

As the classical historian Theodor Roszek said of a very different time, “All revolutionary changes are unthinkable until they happen…and then they are understood to be inevitable.” In an age where there appear to be no alternatives to the status quo, the rapid demise of the GDR stands as a lesson in how quickly the unthinkable can become inevitable.

Pingback: Both an End and a Beginning: The Long Fall of the Berlin Wall | Superfluous Answers to Necessary Questions

Pingback: This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History | Imperial & Global Forum

Pingback: Sympathy for the Devil: Seeing the World Through the Eyes of the Stasi in Deutschland 83. – Superfluous Answers to Necessary Questions

Pingback: The Constitution Of 1990 | Max Hertzberg

Pingback: Superfluous Answers to Necessary Questions | Max Hertzberg

Pingback: Who Is the Volk? From the Fall of the Wall to Merkel & Me – Superfluous Answers to Necessary Questions

We’re glad to turn out to be visitor on this great website, thanks for this unique information and facts!

LikeLike